More Stories

WASHINGTON - The head of the Food and Drug Administration told lawmakers Thursday that a shuttered baby formula factory could be up and running as soon as next week, though he sidestepped questions about whether his agency should have intervened earlier at the plant at the center of the national shortage.

FDA Commissioner Dr. Robert Califf faced a bipartisan grilling from House lawmakers over the baby formula issue that has angered American parents and become a political liability for President Joe Biden.

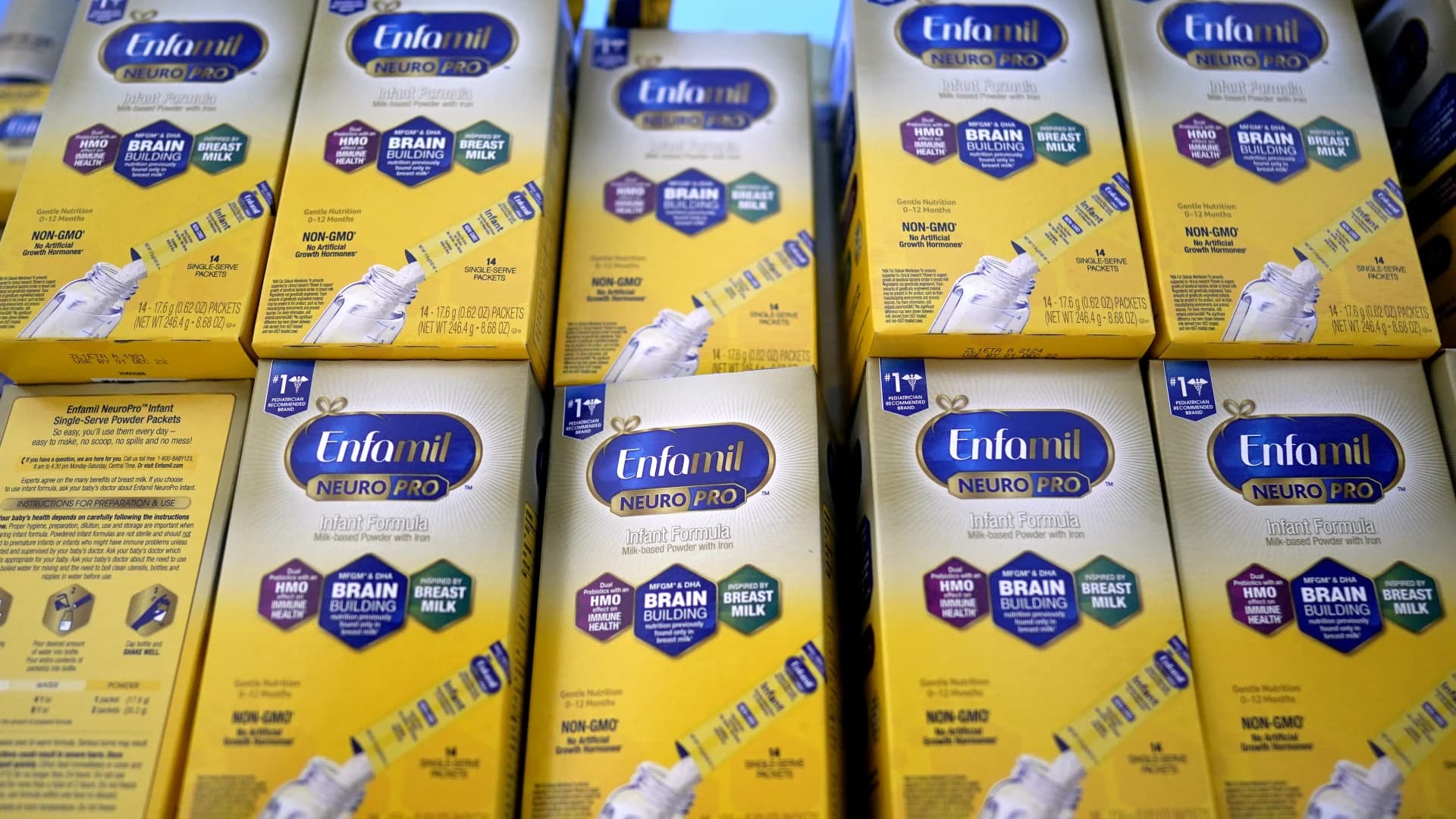

The problems are largely tied to Abbott Nutrition’s Michigan formula plant, the largest in the U.S., which has been closed since February due to contamination problems. The FDA announced a preliminary agreement with Abbott earlier this week to restart production, pending safety upgrades and certifications.

“We had to wrestle this to ground with Abbott,” Califf told members of a House subcommittee “I think we are on track to get it open within the next week to two weeks.”

After production resumes, Abbott has said, it could take about two months before new formula begins arriving in stores.

When lawmakers asked why it took the FDA months to investigate warnings about safety violations at the plant, Califf said he couldn’t say much due to an ongoing investigation into the issues. Several lawmakers rejected that response.

“It’s not acceptable to say you just can’t comment on it,” said Rep. Mark Pocan, R-Wisconsin. “This is a problem I’ve seen over and over with the FDA: You guys aren’t good at communicating."

Califf is the first administration official to testify before Congress on the shortage, which has left some parents hunting for formula and become a talking point for Republicans. On Wednesday evening Biden announced sweeping new steps to improve U.S. supplies, including invoking the Defense Production Act and flying in imported formula from overseas.

Members of the House Appropriations subcommittee opened Thursday’s hearing by asking Califf why the FDA didn’t step in last fall when there were warnings about problems at the Sturgis, Michigan, factory.

Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Conn., pointed to a recently released whistleblower complaint alleging numerous safety violations at Abbott’s plant, including employees falsifying records and failing to properly test formula before releasing it. She said the former Abbott employee alerted the FDA to the situation in October but was not interviewed by agency staff until late December.

“It all begs the question, why did the FDA not spring into action?” DeLauro asked. “Who in the leadership had access to that report — who didn’t have access to the report — and why was there no reaction?”

Califf said he had reviewed the complaint but didn’t specify when or what immediate steps were taken. He said the allegations raise serious concerns about Abbott’s operations.

“The most concerning charge is that the integrity of the organization was compromised,” Califf said. “Once that integrity is compromised the question is how can you trust any of the systems that are in place.”

Subcommittee Chairman Rep. Sanford Bishop, D-Georgia, called the lag in FDA action “unconscionable.”

“American people rely on FDA to protect infant health by ensuring that they have access to safe formula,” Bishop said.

Abbott shut its Michigan plant in February after FDA inspectors began investigating four bacterial infections in infants who had consumed formula from the plant. The first of those cases was reported to the FDA in September though agency staff didn't begin inspecting the facility until late January. Califf said earlier this week the agency's investigation is ongoing and it hasn't yet reached a conclusion on whether bacteria from the plant caused the infant infections.

Abbott has said there is no direct evidence linking its products to the illnesses.

The baby formula shortage is the first major crisis for Califf since returning to the FDA in February. He briefly led the agency under President Barack Obama and was tapped for the job again based on his past experience leading the sprawling agency, which regulates food, drugs, medical technology and tobacco.

Thursday's hearing was scheduled to review the FDA's budget request for next year, and Califf asked lawmakers for $76 million in new funding for food safety and nutrition.

“I was very well aware coming in that we need to do major improvements on the food side of the FDA -- not because the people are bad -- but there is a need for consistent leadership and the right resources,” Califf told lawmakers.

The funding request comes amid longstanding concerns that the FDA's food program — which oversees most U.S. foods except meat, poultry and eggs — has been underfunded compared with the agency's drug and medical divisions.

On Wednesday evening, House Democrats passed a $28 million spending bill that would boost FDA funding to inspect domestic and international formula producers. It's fate in the Senate is uncertain.

More from News 12

1:49

Yorktown board members reject controversial cell tower proposal

2:21

From warm and sunny, to cool and rainy

1:29

Residents, drivers divided on condition of Putnam County road as town works on improvements

1:53

Mount Pleasant settles voting rights lawsuit, shifts toward district elections

0:50

Driver critically hurt after Jeep became submerged in Lake Mahopac is dead

2:25